In the first part we have discussed what is critical thinking and how to get clarity by asking right questions. It is important to get clear on a problem or request but it doesn’t move the needle. To perform prioritization we need to come to conclusions. In the second part we will talk about how we arrive to conclusions and how personalities affect this process.

Everybody heard that it is bad to assume and we shouldn’t jump to conclusions. I believe it is misleading idea and doesn’t help at all. It is very rare situation when the one has all information about a problem or request and doesn’t need assumptions. Moreover if you will wait for all information to be available, you most probably will lose momentum and be late with decisions. We need assumptions the same way we need facts and observations. However, there is a huge distinction between automatic thinking and critical thinking assumptions.

In the end, it is all about premise and its building blocks.

How strong is your premise?

There are two major different ways how we come to conclusions – deduction and induction. The first one goes from generics to specifics, the second one vice versa. However, it is easier to explain on examples.

The initial statement in deduction is general truth. Based on that truth, we can determine specific instance is true as well.

“Every new customer support ticket should be assigned to an engineer. The new support ticket just came in, so an engineer should be assigned”.

With deduction everything is black and white. There are no “if” or “but”, no argument or deviation. And it is far from reality. In the real world everything is “almost” – “almost always”, “almost never” and etc. That’s why in personal and professional life we use induction.

“Our customers are complaining when we raise our prices. We are raising prices soon, so customers will complain.”

“Everytime I go to a meeting with Sales Engineers, they ask for a roadmap. So, I need to prepare roadmap slide deck for the next meeting.”

The premise of inductive reasoning consist of multiple individual instances – many times, a set of experiences. This allows us to generalize all future instances. The more previous instances we had in the past, the more confident we are in the future outcome.

If one customer report of a degradation of you application performance, you will not run immediately to Engineering screaming for a help. If 100 customers reported the same issue, you will run to DevOps or Operations team as fast as you can because most probably there is a large scale problem.

The initial set of statements here is a premise (100 customer submitted ticket with same symptoms) and the outcome (there is a problem with performance) is the conclusion. The stronger the premise, the more probable the outcome.

In the context of prioritization, it means assessing a level of impact and probability of customers’ issues or requests.

“- What makes us believe that feature XYZ is important?

– We have received request for it from 20 customers and we expect to receive more.”

So, in order to be confident in our conclusions we need to measure how strong the premise is.

Premise building blocks

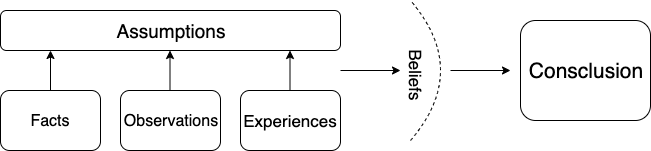

The picture below represents building blocks of premise.

Let’s go and analyze them one by one.

Facts

Facts are absolute truth. With facts, there is no debate. However, there are not many facts. When somebody is saying “Here are facts”, it is not uncommon that in reality those are not facts. If something is repeated many, many times, it does not become a fact either. “Our company is great in quality assurance process” – says CTO. It might be a fact but unless you know that this information is tru, you cannot consider it as fact.

Facts are very important for the premise. Because they are absolute truth, they make your premise strong. If you based conclusions solely on facts (though, it is very uncommon situation in reality), then your conclusion is correct.

The other thing about facts – they cannot be about the future. There is no guarantee that even the sun will shine tomorrow again, it is extremely probable instead.

“Customer will launch new service next quarter.” Is that a fact? No. There are multiple reasons why customer will not do it.

“On the last cadence call customer said that they are unhappy with our roadmap.” It is a fact that customer said that they are unhappy. But are they really unhappy? There are also too much definitions of unhappy. So, anything that generates a discussion is not a fact.

“If we will not deliver this feature next quarter, customer we will loose RFP.” Fact or not? No, it is not a fact. It is about future and we cannot be 100% sure about it.

“Today it takes around 2 months to deliver new feature”. Fact or not? If input data is correct, it is a fact then.

Observations

Observations is information that we receive from everything we read, hear or see. We don’t know if observations are absolutely true and we don’t experience them ourselves. When you ask somebody a question, a person’s response is an observation.

In fact, most information that we receive from customers are observations. We don’t know if they are true, how data was collected and was it delivered completely to us.

There is always a confusion about facts and observations. We tend to add weight to information that we receive from people we know, who are close to us or have higher authority. However, it doesn’t convert an observation to a fact.

While asking clarification questions to customers, it is important to access credibility of the source. If CEO tells you that company has strategy to move 80% of workloads to cloud in 2 years, then it worth start looking into increasing your cloud skills. If you see the same message posted in social media by random analyst, you will have doubts about it.

To distinguish facts from observations it is enough to ask simple question: “Is this information absolutely true, with no question, no discussion, no explanation, and no variation?”. If the answer is no, it is an observation.

Let’s say Engineering manager says “Our development team is motivated”. It is possible that some employees are indeed motivated, while it maybe not a case for others. This statement requires some discussion to understand reality. It is an observation.

You can use techniques described in Part 1 to get clarity on observations. Our premise for customers’ requests prioritization is mostly consist of observations, so it is important to know what is a possibility that they are true.

Experiences

Experiences are valuable assets in the thinking process. It is something that we done or witnessed ourselves and it has great impact on our decision making. If you were there, if you did before – it is an experience.

Experiences can only be from the past. The common fallacy here is that our brain change our memories, it removes some pieces and distorts others. Be aware about that. The same situation may have orthogonal experiences for two different persons.

The other issue with experiences – we trust them too much. If you are solely base prioritization on your experiences (Been there, done that), you narrow view a lot and missing important context. On the other hand, experiences are reliable sources of information – the more experience you have with a particular issue, the stronger your premise will be.

So, looking on the list of issues, try to “empty the bucket”. Don’t focus too much on what have happened before, just keep it in mind to find a pattern.

Beliefs

Every each one of us has set of core values. Many of them are share, some are unique. These values or beliefs is something that does not depend on circumstances. They are constant in our personal and professional lives. It is an emotional part of thinking process.

People who value quality over quantity will come up with different priority list than people who believe that quantity prevails. We may even filter and discard some information if it contradicts our beliefs. And it takes a long time to change a it – a lot of experiences and messages are required to move a needle in such deep-rooted thing as believe.

Understanding our beliefs doesn’t remove emotion, but it allows us to recognize how they influence our conclusions—which gives us a more thoughtful perspective of those conclusions. So, don’t try to fight them, be aware about this part of the premise and observe what impact do they bring.

Assumptions

Our world is full of ambiguity. Information we receive is rarely full or absolutely true. So, in order to come to conclusions we need assumptions. An assumption is a thought you have and presume to be correct. Based on that, you can come to a conclusion.

However, in automatic thinking mode you presume that your assumption is correct. In critical thinking mode, you ask “How do I know that my assumption is a good one?”

The rule of thumb for assumptions is “Don’t make assumptions without knowing how you arrived there or make assumptions you cannot validate.”

Assumptions are formed by facts, observations and experiences. If an assumption is based on facts that are not facts in reality or on observations that are coming from unreliable source, or on a single experience then an assumption might be not a good one.

Let’s have a look on an example.

Our Professional Services team is waiting for pre-requisites to be fulfilled before project kick-off. You receive an update from customer that everything will be ready in 2 weeks. However, you previous experiences show that the customer was late last 10 times. So, observation you received contradicts with your personal experience. So, premise for an assumption that customer will be on time is less reliable that an assumption that we should add 2 weeks for contingency.

We make countless assumptions in automatic mode. But in critical thinking, we don’t take our assumptions for granted. We ask what facts, observations, and experiences we are using to come up with these assumptions. Can we validate or invalidate these assumptions by gathering additional observations? Do others have different, contrary experiences?

The Conclusion – Putting it all together

Now, we are ready to come to conclusions. We got clarity on customer request, we collected facts and observations.

Facts, observations and experiences are foundation of assumptions. We then apply our belief filter to yield a conclusion and figure out what is important and what is not..

Here how it works.

Situation – “Our Big and Demanding Customer (BDC) wants us to deliver feature XYZ before Christmas”

Fact: The customer is in top 10 customers of the region

Fact: Sales pipeline indicates 100M$ opportunities for this year

Observation: Our champions in customer’s organization expecting us to commit for feature delivery

Observation: There is a probability to loose RFP to a competitor

Experience: The customer placed an order last 5 times we delivered new functionallity

Belief: It is right thing to fulfill requests from existing customers

Conclusion: Feature XYZ is a priority for development team

For prioritization purposes our conclusion should be clear understanding if a request is important and why.

The stronger the premise, the more confidence you’ll have in your conclusion. Conversely, if your premise is weak, your confidence in your conclusion is lower. Consistent facts, observations, and experiences provide strong premise components, and strong premises contain assumptions that you can validate. Weak premises, on the other hand, have assumptions that you cannot validate—because they aren’t supported by facts, observations, and experiences.

Very analytic people weigh facts very heavily. Some people will have an experience only once and weight it very heavily. Our personalities influence our inductive reasoning and our premises. We all use the same process to think—but we weigh premise components differently, which results in different conclusions.

Examine your premise, make sure that facts are facts. Try to collect observations and experiences that are consistent with each other. Pay attention to how your beliefs impact your thinking process. And always ask yourself a question “What assumptions am I making and why?”

Now real prioritization starts!

We came to understanding what is important and what is not. Most probably we have a long list of items. But the good news are – it is clear why something is in the list, we understand credibility of our assumptions and level of confidence of conclusions.

After all heavy lifting is done, we are finally ready for prioritization. This will be our topic for final part – Decisions.

Feel free to subscribe below to get notification when it will be published!

Follow me on Social networks: